Testing.

The very word conjures up emotions in students and parents and school officials alike. Within the educational community, this word conjures up other words like: measuring, accountability, fairness, purpose, practice, instructional time, online, paper/pencil, formative, and summative. Your connection to these feelings and issues probably shapes your views about testing in our public schools. Part of what makes this such a big issue is that there are no simple "right" and "wrong" solutions. It is a complex problem that requires thought and discussion among many stakeholders.

The goal of schooling is learning. There may be other benefits such as socializing, joining a club or team, earning a diploma; but the goal is learning. Our ability to measure learning has grown significantly over the past twenty years as educators come to understand the value of frequent formative assessments in combination with teaching strategies that engage students. In the past, the school classroom was a very dictatorial place: Teacher in the front doing most of the talking; students sitting in rows listening to the teacher and taking notes; test or quiz every Friday. This system worked fine for the student who was able to learn by listening, but if you needed to ask questions, or clear up any confusion with the content prior to the test you probably struggled to learn in this environment. And if you weren't able to concentrate on the teacher's words for two or three hours, you might have missed your first and only chance to get that precious information from the teacher.

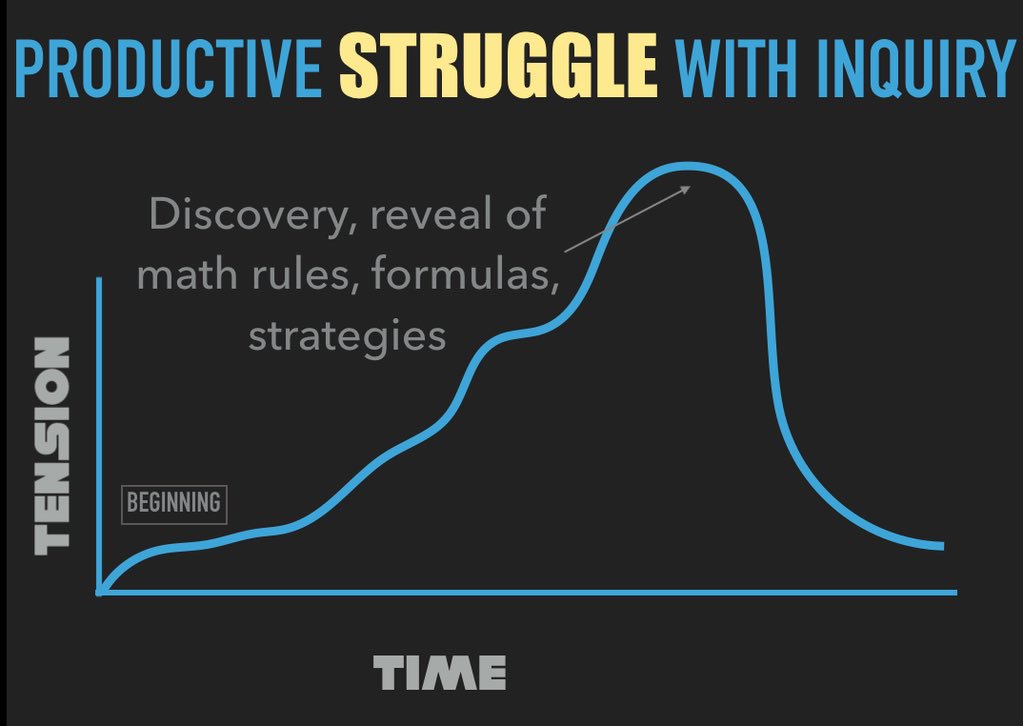

Today we know that learning requires doing and talking and questioning in addition to listening (and note taking). We also know that we want to get a sense of the learning that is taking place on a daily basis and not just once a week or whenever the "Big Test" occurs. This "measuring of daily learning" is what we call

Formative Assessment. It could be a game, a series of verbal questions from the teacher, an activity during class, a

exit ticket (or exit pass), Anything that gives the teacher and the student information as to their level of understanding the content or the objective for the day. Usually when we argue about "Testing", this isn't the sort of testing that we are arguing about.

The discussion over testing usually centers around what educators call summative tests. These are chapter or unit tests, final exams, end-of-course tests, and major state tests. These tests might be required to graduate from high school; or they may command a large portion of a final grade in a course; or they may be used to determine if you are ready for college (or if you will be accepted to college). These are the tests whose results have some sort of consequence.

A common issue that arises is a student who appears to be learning very well based on class grades and report card grades, but then this same student demonstrates a lower level of learning on one of these big tests. I think that I worry when there is a public outcry over testing because of this scenario. I feel that rather than arguing against giving the test, we should question why the discrepancy happened in the first place. Clearly a student who fails an end-of-course test and earns an "A" or a "B" as a course grade cannot (both) be very knowledgeable about this content AND be very weak with this material. Something is going on. Perhaps both the course grade and the test are not true reflections of the student's ability. Perhaps it is somewhere in the middle of these two extremes.

Since the goal of school is learning, there should be accurate and valid methods for determining the extent of this learning. It isn't enough for a student to come to school everyday and do what he's told to do and then walk out of school without some measure his learning. Getting grades isn't enough. What does it benefit a child to get good grades in school and not be able to read or do math at an acceptable level when he leaves school? This is one of the reasons for instituting summative and state testing in the first place. Also far too many students begin college but

never finish college. If more people took the results of these big tests seriously, they might be less in a rush to go to college until their abilities were more in-line with college-level expectations.

Is there too much testing? Why are you asking this question? If it is because you don't like to see your child getting poor results on this test, than you should question the discrepancy between the course grades and the big test. If it is because the results are not used for any useful purpose, then you should discuss this with you child's teacher or school. Everything done in public schools should have a purpose; this includes testing.