There's a joke among some educators that says if a child doesn't understand the lesson, then we will just say it again slower and louder.

There's a joke among some educators that says if a child doesn't understand the lesson, then we will just say it again slower and louder.It's not a funny joke. In fact its really sort of a put down to teachers who struggle to help students to learn. If the teacher presented the lesson in the best way she knows how, then she may not know of another way to present the lesson and (so) when a students doesn't get it, she just repeats the same thing (sometimes slower and louder). This usually doesn't help the student to learn any better than the first time, but it does lead to frustration for both the student and the teacher.

These situations are far too common in our nation's classrooms today. Improving these situations is haphazard at best. Sometimes some students try harder; sometimes some teachers try different strategies. But most of the time, instructional change is small (or absent) and academic results remain the same.

Still, this doesn't happen from a lack of trying. Plenty of teachers (most teachers) try very hard to learn more and to improve every year. They read books; they attend conferences; they take classes; they join Professional Learning Communities (PLCs) within their school or school system or online.

Still, this doesn't happen from a lack of trying. Plenty of teachers (most teachers) try very hard to learn more and to improve every year. They read books; they attend conferences; they take classes; they join Professional Learning Communities (PLCs) within their school or school system or online. Change is hard, and improving academic results for student groups that have historically struggled in the traditional school system is a complex problem. It isn't the sort of problem that can be solved by tinkering around the edges; and by not causing some level of discomfort for people who insist that everything is fine the way it is now.

I believe that we have the knowledge and the research to know what must be done to improve education outcomes for the students that we aren't reaching today. These strategies and policies are available for everyone to see. A short list of books from a variety of sources provides the answers we seek. Here are some of them:

- The Results Fieldbook: Practical Strategies from Dramatically Improved Schools, by Mike Schmoker

- Whatever It Takes: How Professional Learning Communities Respond When Kids Don't Learn, by Richard DuFour

- School Leadership that Works: From Research to Results, by Robert Marzano

- Teacher Leadership that Strengthens Professional Practice, by Charlotte Danielson

- Failure is Not an Option: Six Principles that Guide Student Achievement in High-Performing Schools, by Alan Blankstein

However, I also believe that the change we need involves the hard work of constant improvement. It requires schools to dig deep into the standards and objectives that are taught everyday and to ask questions such as,

- What is the best way to teach this objective to students?

- What strategies should we use?

- What activities are best?

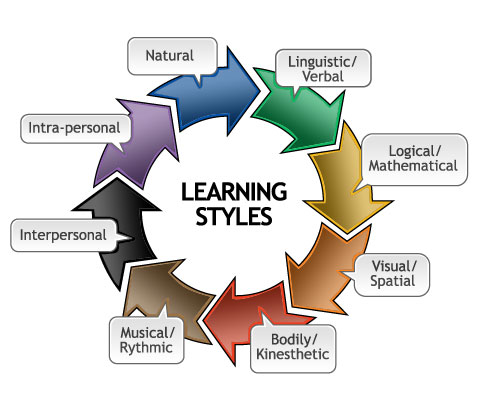

- How do we reach a classful of students with different learning styles?

- How do we assess student understanding?

- How do we assess the success of the decisions we made for this lesson?

This is complex work and it requires effective collaboration among teachers--no one should have to do this on their own. If we are successful, it will take a generation to complete this transformation of our schools. During that time, we will have to contend with a lot of resistance from educators and non-educators alike. However, this is an effort that is worth the years of hard work. This is an effort that today's teachers can look back on and be proud to say, "I was there when the hard work was done."

Tinkering around the edges isn't enough anymore. It's time to do what we tell our students to do--Work hard and you will see the rewards in your future.