So why am I (a lifelong educator) writing about not going to college? Because public school desire to teach ALL students. All students are welcome in our public schools. We take all students. We don't have some sort of litmus test that permits some students to enter our public schools and denies others t enter; we take everyone. And in doing so, we have an obligation to teach all students. This means that we teach the students who are college-bound as well as those that are not. This leads to the dilemma of all public schools: Are we preparing students for college? Are we preparing them for the world of work? Or, Are we doing both? (And if the answer is the latter, then How do we do that?)

We know that all students won't go to college. (source) We also know that some will go to college and won't finish college. (source) Here is a slideshow of 25 jobs that don't require a college degree--although nearly all (or actually all) of these jobs require some sort of education and/or training beyond high school. So the question remains, How do prepare the college-bound students and the non-college-bound students at the same time?

The simple answer is that this is a complex problem. It is a problem that (in my opinion) requires multiple options and pathways for high school students. It is a problem that does not lend itself to one-size-fits-all solutions.

It is fair to say that all public schools recognize this need to prepare students for their lives beyond high school--whatever they may be. But it is also fair to say that some requirements are aimed (more) at the college-bound students than at the non-college-bound students.

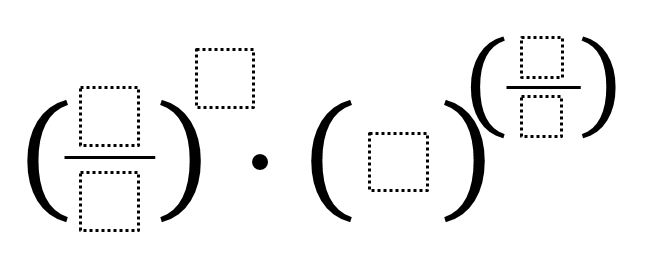

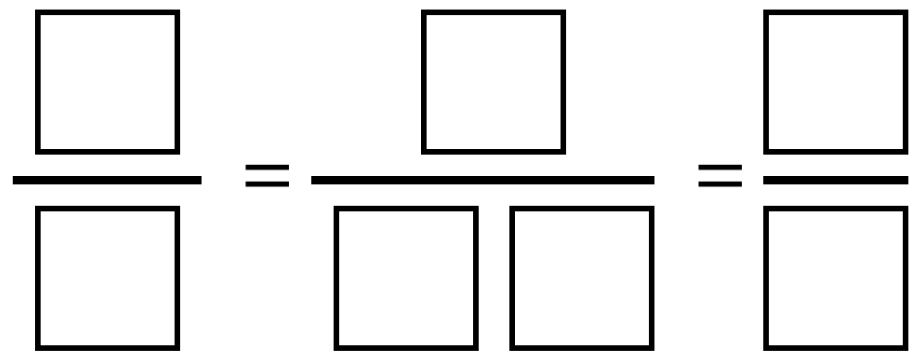

My solution views these two subgroups of students as much more alike then different in terms of the skills and knowledge that they need for both college and work. Clearly, reading and basic mathematics understanding is needed. By "reading", I include understanding the context of what is being read; and I include reading and understanding non-fiction and technical manuals. Our civilized world requires reading. Medical reports, insurance papers, legal documents such as wills and mortgages all require a level of reading in which people can read and understand. By "basic mathematics", I include understanding and calculating things such as sales tax and interest income. People should be able to gain information from a chart, graph, or table of numbers. People need to know what a percent means and what fractions mean. Calculators can do the calculations, but people need to do the "understanding". Beyond reading and mathematics, I believe that a good understanding of other typical high school subjects is needed to help people gain an understanding of the world and the people around them. These include science, history, art, some computer skills, health, and knowing a foreign language--which is extremely common outside of the United States.

My solution views these two subgroups of students as much more alike then different in terms of the skills and knowledge that they need for both college and work. Clearly, reading and basic mathematics understanding is needed. By "reading", I include understanding the context of what is being read; and I include reading and understanding non-fiction and technical manuals. Our civilized world requires reading. Medical reports, insurance papers, legal documents such as wills and mortgages all require a level of reading in which people can read and understand. By "basic mathematics", I include understanding and calculating things such as sales tax and interest income. People should be able to gain information from a chart, graph, or table of numbers. People need to know what a percent means and what fractions mean. Calculators can do the calculations, but people need to do the "understanding". Beyond reading and mathematics, I believe that a good understanding of other typical high school subjects is needed to help people gain an understanding of the world and the people around them. These include science, history, art, some computer skills, health, and knowing a foreign language--which is extremely common outside of the United States.Beyond these academics, I believe that the rules and regulations that take place in a high school and in the classroom should instill in our students a sense of right and wrong as well as a sense of how to exist as an adult in society. When my daughter was in kindergarten, her teacher told us that everything they do has a purpose. What may look like "fun" or "downtime" to the non-kindergarten-teacher observer, has a purpose. Similarly, everything in high school should have a purpose. Whether you are going to college or work, you need to be on time, you need to be polite, you need to listen. You need to learn from others and you need to be able to work with others. You need to know that sometimes you'll get some help to do things and sometimes you have to do things on your own. You need to be responsible and you need to take on responsibilities.

It seems to me that when employers complain about young people in the workplace, it isn't so much that they lack reading and mathematics skills--although I hear this as well. It is more that they lack the ability to accept responsibilities, to understand written and verbal directions, and to follow through on important tasks. These skills are needed for the college students also.

College isn't for everyone. But public schools and their graduation requirements and daily rules and regulations are for everyone. Learning is a lifelong skill. It doesn't stop on graduation day. We want all students to succeed regardless of the path they take after college.